Quasicrystal

Hagoromo: In Search for the textile with ultimate beauty and function

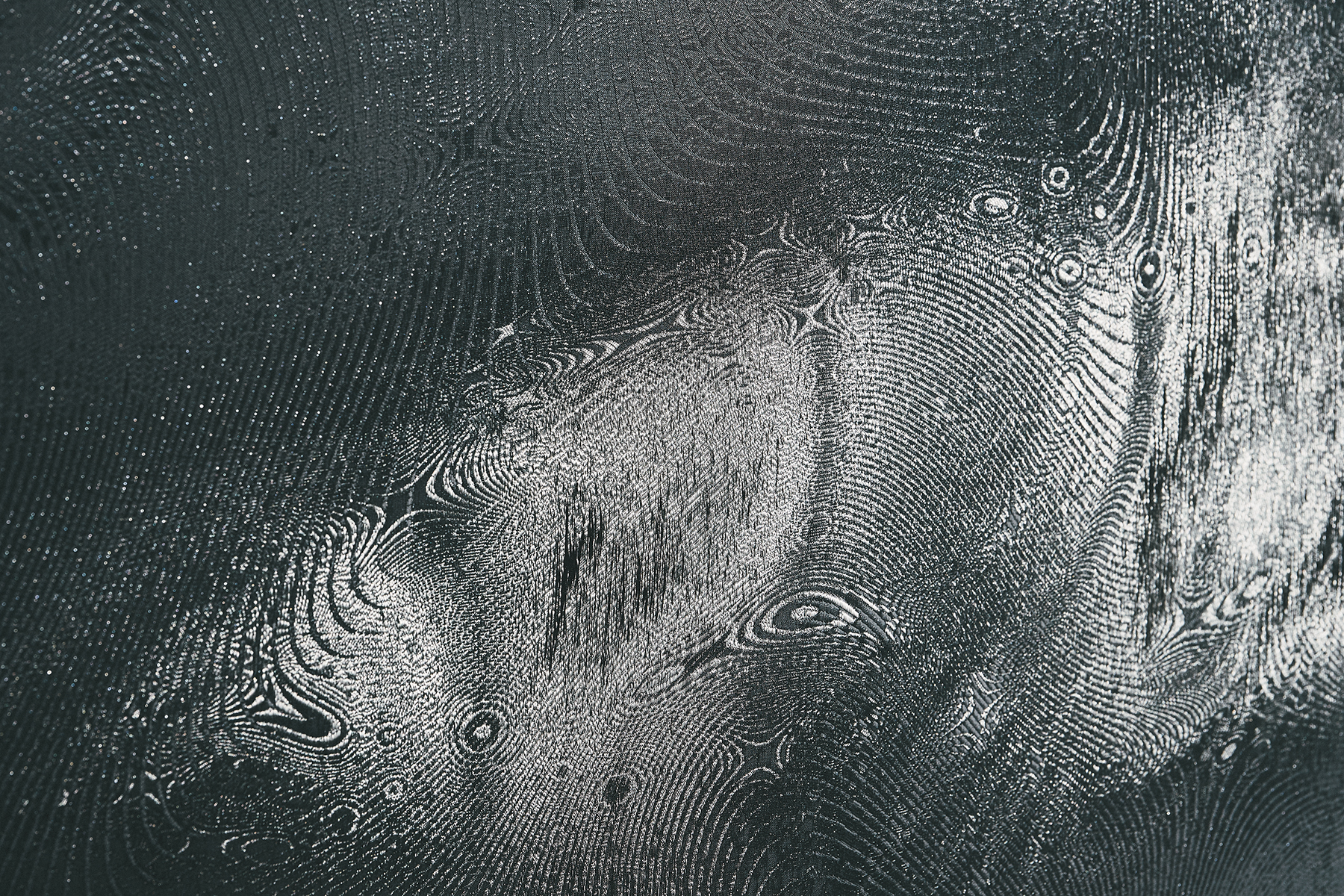

Quasicrystal

Quasicrystal and Textile

Idaka: Tell me about the title, Quasicrystal, and what the project aims to challenge, or explore, in the world of textile.

Furudate: In textile weaving, there are three basic weave structures: plain weave [hira-ori], twill weave [shamon-ori/aya-ori], and satin weave [shusu-ori]. There is only one type of plain weave and several types of twill weave. For satin weave, there are many variations. Textiles are basically made up of a combination of these three weave structures. Also, the smallest unit that is repeated when making a textile is called the “weave repeat.” Textiles are based on this unit, which allows the yarns to entwine properly. I thought that, by using a computer, I could deconstruct the weave repeat, pick out the most basic rules of warp and weft yarns intersecting to form a surface, and weave fabric using only those rules. But, composing a textile with only the weave repeat limits the level of detail. For example, if a fabric had 200 warp yarns, and a weave repeat consisted of five warp yarns, you only get 40 parts (200 divided by 5), meaning you can only control the pattern in a unit of 40. My initial idea was to use a computer to make the yarns intersect only horizontally and vertically so that I could tweak the design in a more detailed and organic way. In this way, I tried to deconstruct and reconstruct, using a computer, the historically-created concept of weave repeat and recreate a computerized method of weaving, or rules, at the smallest level.

Regarding the project’s title, Quasicrystal, crystals are a state in which the structure of the metal is repeated in a neat, grid-like pattern. This is called translational symmetry, and even if you shift them around, they always overlap. It means that the crystal’s structure is systematically repeated. On the other hand, an amorphous state has no order at all. Crystals include iron, etc., and amorphous materials include water and, for solids, glass. Glass does not have a crystalline structure.

In contrast to these two, quasicrystals have a certain order but not translational symmetry, and if you shift them, they do not overlap. If you look at it from a microscopic point of view, it has a regular structure, but if you look at it from a macroscopic point of view, you can’t find much regularity.

The textiles that Hosoo typically produces are “crystalline” created based on the weave repeat. They have stable structures that are lined next to each other. What we are trying to develop is quasi-crystalline, something that creates a new order without using the weave repeat.

Idaka: I remember the story about the pieces you created for Fabrics as Demiurges (Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, 2017). You tried weaving randomly but ended up with messy pieces, and that you reached a dead end, realizing that the weave repeat, which humans had been producing for thousands of years since the beginning of history, was indeed beautiful.

Furudate: That’s right. First, to weave fabric using a computer, I wrote an actual program and tried weaving randomly to see if it worked. It was before I figured out the relationship between an algorithm and the resulting fabric, so I tried an easy way, which was to weave randomly. I tried it and found out that the result was utterly boring. When I compared it with Hosoo’s collection, the actual products, I realized that it was necessary to have an order. Plain weave is really powerful. If you try to understand the functionality of textile at a microscopic level, you arrive at the plain weave. The vertical and horizontal are intertwined in a one-to-one relationship. The result is inevitable. I wondered what I could do to such a complete thing and came up with the idea of using a weave structure, like satin weave, as a base, adding variables to it, and shifting it little by little. My initial method was to use an existing order as the basis and modify it. Later, when we invited three artists to Quasicrystal, we found other methods, but this was my first step.

Idaka: You needed some order, and that was how you arrived at the concept of “quasicrystal.” Now, I understand that Mr. Hosoo has been interested in the question, “what is beauty?” What I felt through this project was that to find the answer to this question, you must first go through a process of creating things that are not beautiful. The mission of Hosoo Gallery and Hosoo Studies is to explore the beauty. I would be happy to hear your thoughts on the question of what beauty is at this point in the project.

Hosoo: As Mr. Furudate mentioned, in the world of textile, you begin with plain weave. Since the beginning of history, what started with plain weave evolved into something physical and then into twill and satin weaves. Based on this equation, beauty was developed over thousands of years. It is similar to the twelve-tone scale in Western music. Mr. Furudate’s initial attempt was like ignoring a musical scale and hitting random notes. That way, you end up with noise. What is interesting is that, on the one hand, there is a musical scale that feels comfortable to our modern ears, but on the other hand, there are di erent types of beauty, like gagaku [Japanese ceremonial court music]. So, there is the twelve-tone scale for music, and for textile, there is the weave repeat, but there could also be a beauty that humans have not yet discovered. And, that is what I’d like to explore. Of course, the crystalline beauty that has been developed over thousands of years is extraordinary. Mr. Furudate’s approach is to use such beauty as the base and modify it to find something new, and other people have their own approaches. In recent years, I think those of us in the textile business have been focusing on how to hone our techniques and create something new within the frame similar to the twelve-tone scale in Western music. In the history of Nishijin textile, too, we have been following a linear path, although there were technological revolutions such as the Jacquard loom, a predecessor of a computer. In that sense, I believe the most crucial point of our project is to bring the products of a computer ― programming and other cutting-edge technologies ― back to textile to explore the beauty and its equation undiscovered in the past thousands of years.