RESEARCH

Study on Yūsoku Orimono

Study on Yūsoku Orimono

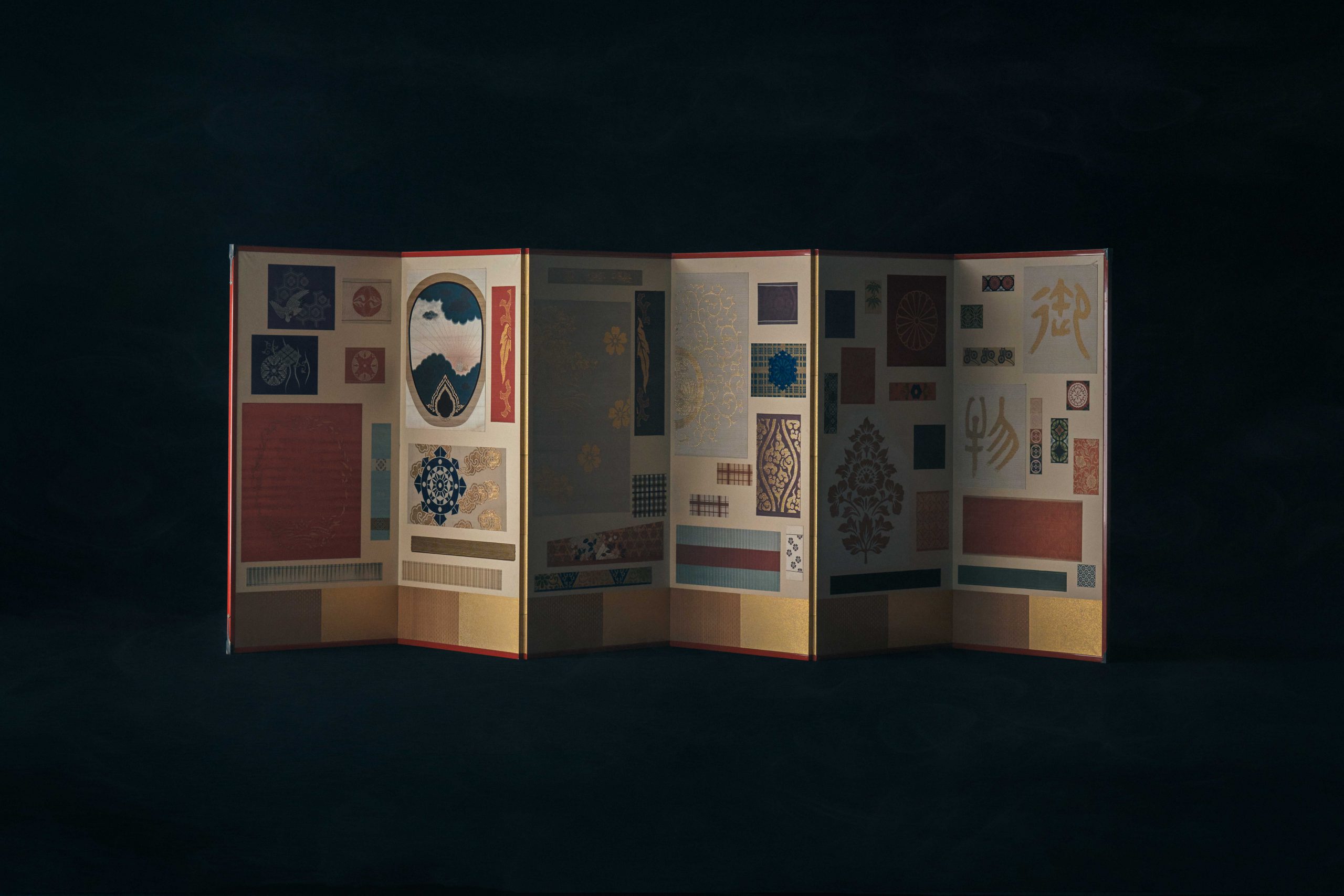

Longevity Screens

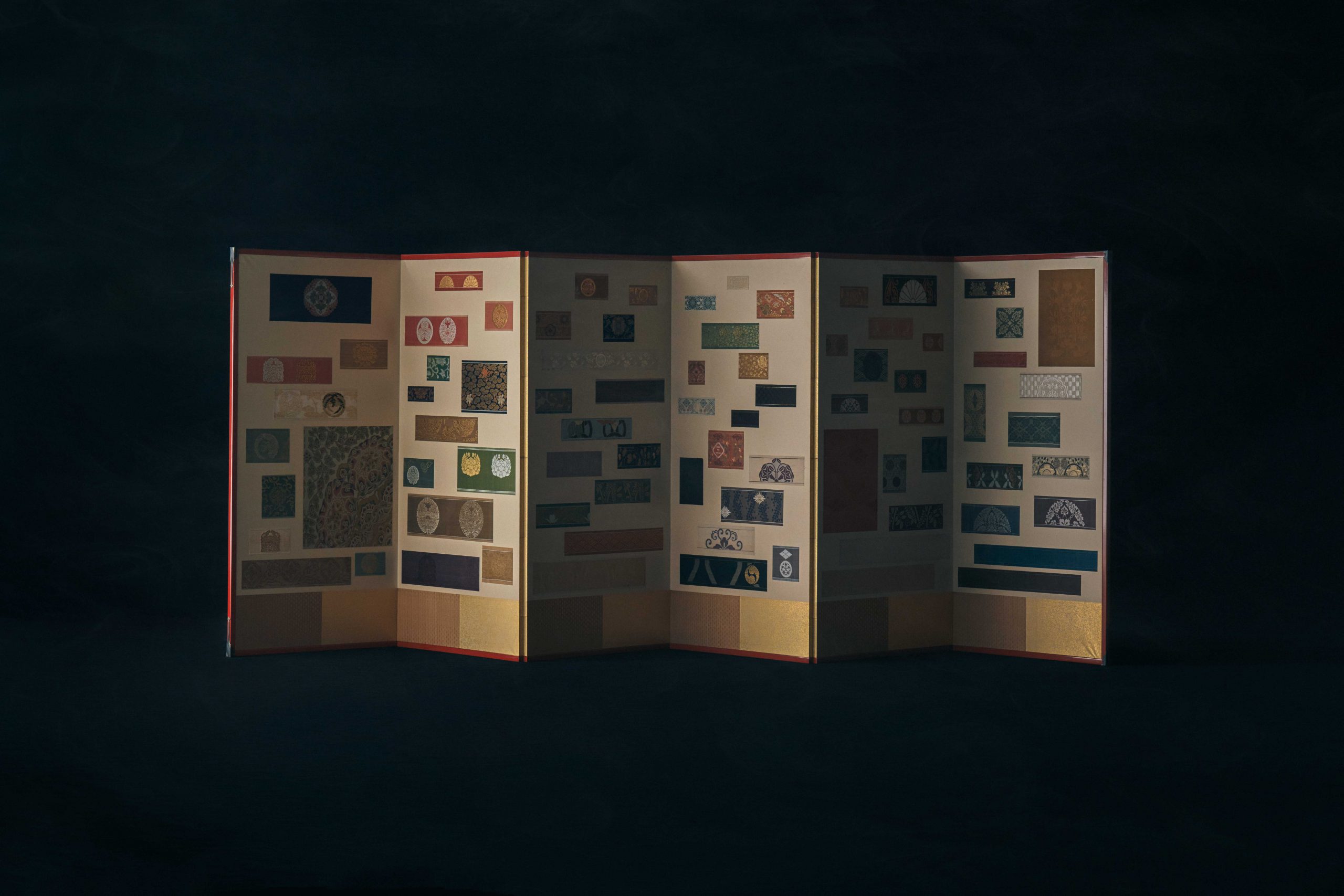

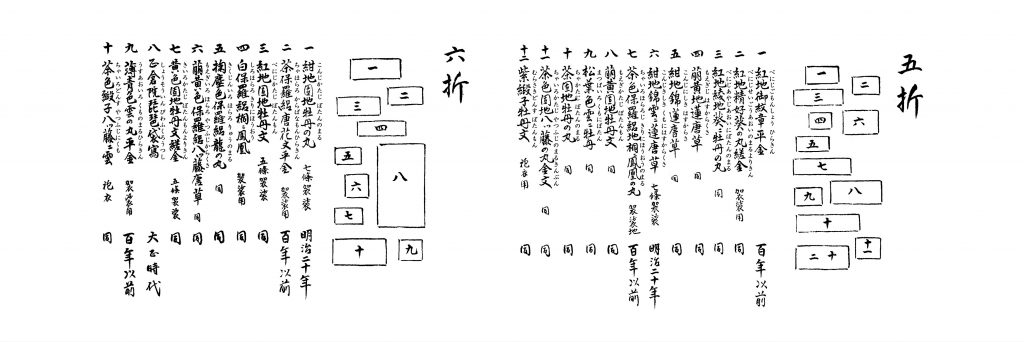

The Hosoo family owns a pair of six-fold screens, a family treasure, that has been handed down in the family. The screens are relatively small—about 120 centimeters tall—but each of the twelve panels is covered with fabric remnants of various sizes, totaling 128 pieces. The screens are accompanied by a document recording their provenance and a separately created handscroll containing explanations of the cloth pieces. The scroll depicts a layout of the cloths on each panel

with cloths’ identification numbers written in Chinese numerals for classification. Furthermore, cloths’ names, orderers, uses, and periods are written in sumi ink, making the screens valuable not only as an art piece but also as a high-quality historical record of dyeing and weaving.

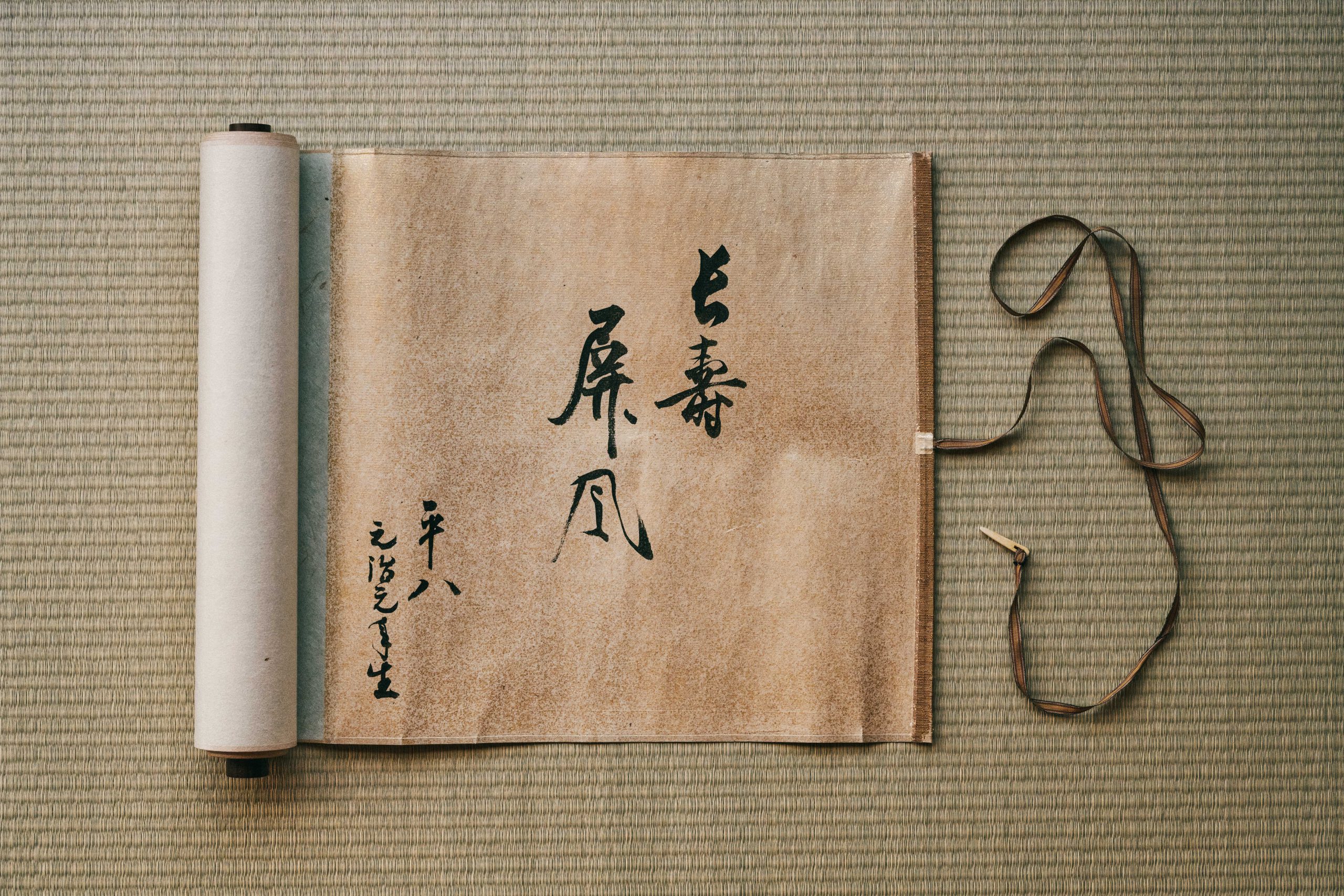

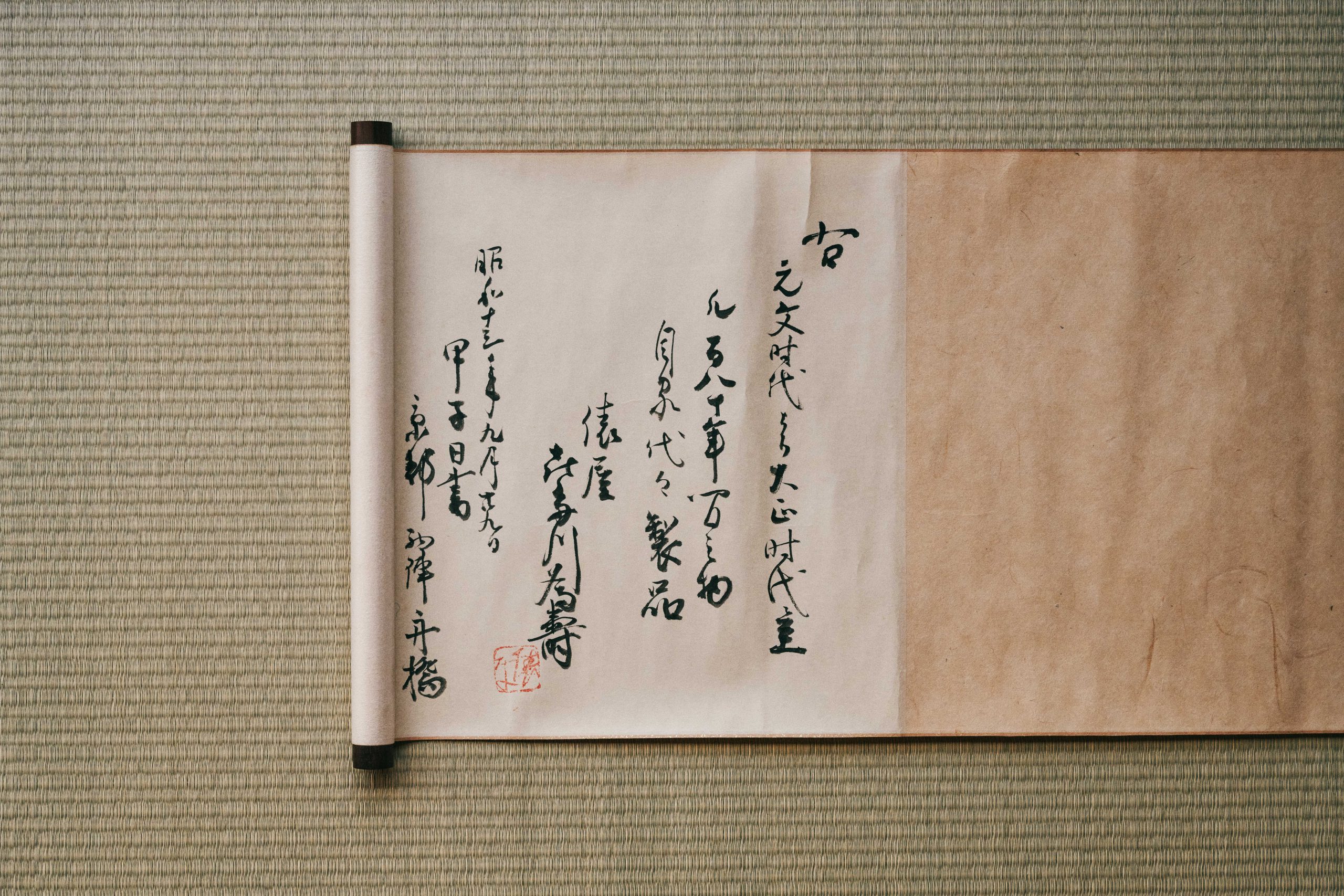

Firstly, we shall trace the screens’ historical background of how they were created and came to be possessed by the Hosoo family. At the top of the handscroll reads “Longevity Screens/Heihachi/Born in the first year of Genji,” and, on the provenance document, it is written “September 29th of the 13th year of Showa,” indicating that the screens were named “Longevity,” signifying a long period of time, and were created in 1938. Also, the name Heihachi suggests the involvement of Heihachi Kitagawa (1864–1940)—a dyeing and weaving craftsman born in the Tokugawa government’s last days—in the production of the screens at the very end of his life. The Kitagawa family is a Nishijin’s prestigious weaver that has traded for 500 years under the name Tawaraya. Toward the end of the

Muromachi period, the family was known as one of the 31 Ōtoneriza families guaranteed the exclusive production of twill. It is also believed that the family was the first to weave karaori [Chinese weave] during the Keichō period (1596–1615). Heihachi, the 15th generation head of the family, was involved in establishing the Nishijin textile model factory in Kyoto during the turbulent times following

the Meiji period. He also produced plantdyed Noh costumes and served as a purveyor to the Imperial Family of the furnishings and costumes for Emperor Taishō’s coronation ceremony, demonstrating his deep insight and skills in weaving. It is said that the folding screens were given to the Hosoo family thanks to its relationship to the Tawaraya Kitagawa family, who married off its daughter (posthumous name: Senshitsu Jukō Shinnyo) to Yashichi Hosoo, the Hosoo family’s seventh head.

Next, let’s look at the details of the fabric remnants covering the screens. Another accompanying provenance document reveals that the cloth pieces were woven by the Tawaraya Kitagawa family during about 180 years between the Genbun period (1736– 1741), the mid-Edo period, and the Taishō period and that the pieces were “pure-type textiles,” or “pure items.” The reason why the family sought purity in textiles is believed to come from the idea that items dedicated to and used at the Imperial Court are untainted and pure, just as Imperial lands are called ōgiyo [great pureness] in the court noble’s language. It can be speculated that, as a purveyor of textiles to the Imperial Family, the Kitagawa family traditionally cherished this mindset.

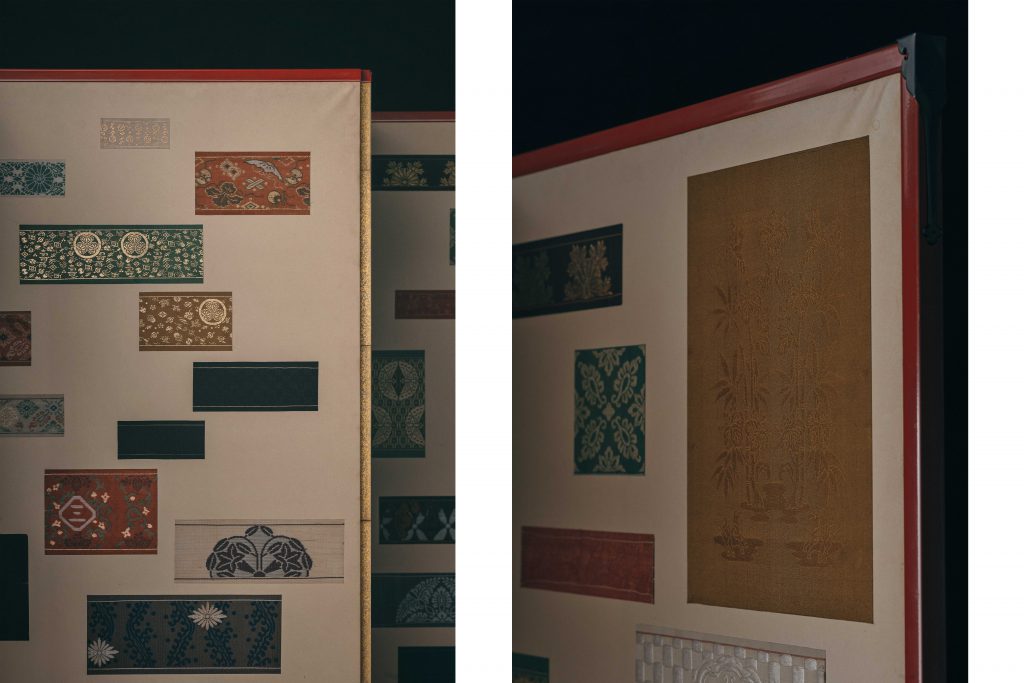

According to the fabric remnants’ age classification found in the handscroll, 82 cloth pieces are “100 years or older,” meaning they are from the Edo period, 25 pieces are from the Meiji period (five are classified as the Meiji period, two as the 18th year of Meiji, four as the 20th year of Meiji, and 14 as the 40th year of Meiji), and 21 pieces are from the Taishō period. In other words, about two-thirds were woven in the mid- to late Edo period. In terms of the owners of the textiles, the orderers included the members of the Imperial Court, such as the emperors and court ladies; court nobles, such as the families eligible for regents; the Tokugawa Shogunate and the daimyō families; Shinto shrines and powerful Buddhist temples, including Ise Shrine, Shimogamo Shrine, and Meiji Shrine; and the Kingdom of Siam (current Thailand). The cloths also include those used for Noh and Kabuki costumes, as well as costume fabrics with tiny patterns used for yūsokubina, a type of hina doll favored by court nobles. The variety of the fabric remnants is so wide-ranging that it captivates the viewers’ attention.

(right)Kōrozen Kiritake Gohō

The following sections focus on some of the fabric remnants and introduce them, with photographs, based on the classification and names written in the handscroll.

The most eye-catching item is a remnant of “Kōrozen Kiritake Gohō,” a kataji-aya fabric, the first piece on the first fold. Hō is the outermost robe of sokutai, a traditional and formal court costume worn by men. The color of the robe indicates the wearer’s rank. Kōrozen is the name of the dyed color. Since the early Heian period, only the emperors have been allowed to wear this unique, yellowish brown, which is also called the color of the sun. Originally, it had been dyed using plants—haze [Japanese wax tree] and suō [sappan]—, but since the modern era, it has been done with chemical dyes. Kiritake describes the pattern on the fabric. The rectangular, box-shaped design combining kiri [paulownia], take [bamboo], phoenixes, and kylins was only used for the emperors as it signified a good omen in the reign of a virtuous emperor. The handscroll notes that the remnant is from the Taishō period, so it is possible that the textile was woven as Imperial property at the time of Emperor Taishō’s coronation ceremony at the Kyoto Imperial Palace. Kōrozen Gohō was also worn by the present Emperor at the Reiwa-period coronation. However, in the past, the attire’s use had not been limited to a coronation and included various ceremonies until the Edo period. Considering that all the other cloth pieces on the screens’ first fold are from the Edo period, the placement of the Taishō-period piece at the very top can be understood as an indication, even in the layout, that it is the most prestigious textile worn by the emperors.

“Shiroji Ōkuchiji Rinpō ni Kumo” is another fabric remnant with a known owner: Ichikawa Danjuro IX (1838–1903). It is the third piece on the screens’ eleventh fold. Since it is described as “Benkei-bakama” [hakama is loose-legged pleated trousers], it is believed to be the ōkuchi-bakama worn when the Kabuki actor played Musashibo Benkei in “Kanjinchō.” With gold horizontal clouds and a dark blue rinpō, a Buddhism symbol, the hakama’s design is suitable for the role of Benkei, a heroic monk.

Danjuro IX was an extraordinary actor famed as gekisei [theater saint]. Together with his

contemporaries, Onoe Kikugoro V and Ichikawa Sadanji I (the three were known as Dan-Kiku-Sa), he dominated the generation. In particular, “Kanjinchō”’s Benkei was one of his most successful roles. In 1887, the first performance with the Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) in attendance was given at the residence of the Foreign Minister Kaoru Inoue (1836–1915). The first play in the program was “Kanjinchō” with Danjuro IX as Benkei, suggesting that he wore, in front of the Emperor, the hakama made with this fabric woven in 1885.

Lastly, let’s examine the remnants from kesa and hōi, garments worn by Buddhist priests, concentrated on the fifth and sixth folds of the screens. The descriptions in the handscroll only state that they are remnants from kesa and hōi, but the woven patterns provide clues to who from which temples wore them. At first glance, the most dominant designs are botan mon [peony crest] (nos. 3, 8, 9, 10, and 12 on the fifth fold and nos. 3, 7, and 9 on the sixth fold) and yatsufuji mon [eight wisteria blossoms crest] (no. 11 on the fifth fold and nos. 1, 6, and 10 on the sixth fold). Daki botan mon [clasping peony crest] is the Higashi Honganji Temple’s crest, and yatsufuji mon has been used as its secondary crest. The temple took a peony as its crest because its successive Monshu [head of a temple] made fictive parent-child relationships with the Konoe family, one of the families eligible for regents, whose family crest was also a peony. The design of the temple’s crest differs from that of the Konoe family’s in details, such as the way the flower core overlaps with the leaves. Among the peony crests found on the screens, daki botan mon (nos. 3 and 10 on the fifth fold) is considered the official crest used by the temple, while there are various other designs such as kani botan mon [crab-shaped peony crest] (no. 8 on the fifth fold), hako botan mon [box-shaped peony crest] (no. 12 on the fifth fold and nos. 3 and 7 on the sixth fold), and kumo botan mon [cloud shaped peony crest] (no. 9 on the sixth fold), which were considered secondary to daki botan mon in their use. All the fabric remnants are believed to have belonged to Higashi Honganji Temple’s Monshu, revealing the deep relationship between temples, especially Higashi Honganji, and the Nishijin’s weavers.

All these fabric remnants speak to us of the dignity and beauty of the best textiles nurtured over many years in Nishijin and their histories and techniques handed down from generation to generation. The remnants reaffirm that textiles have reached the level of art, beyond mere clothing or furnishing materials, thanks to the patrons such as the Imperial Palace, the Shogunate family, and monzeki temples [temples whose head priests are members of the Imperial family], who ordered textiles with refined attention to designs and colors, and the Nishijin’s weavers who continually fulfilled their requests. Furthermore, these cloth pieces convey the attitude of their makers who constantly and bravely challenged new eras, while overcoming the surging swell that occurred during the transition from the Edo period to the modern period, and their sense of mission to preserve and pass on the records to future generations. The value of the folding screens is further defined precisely because it is owned by the Hosoo family, who continually weaves history in our time.