Ambient Weaving

Dialogue

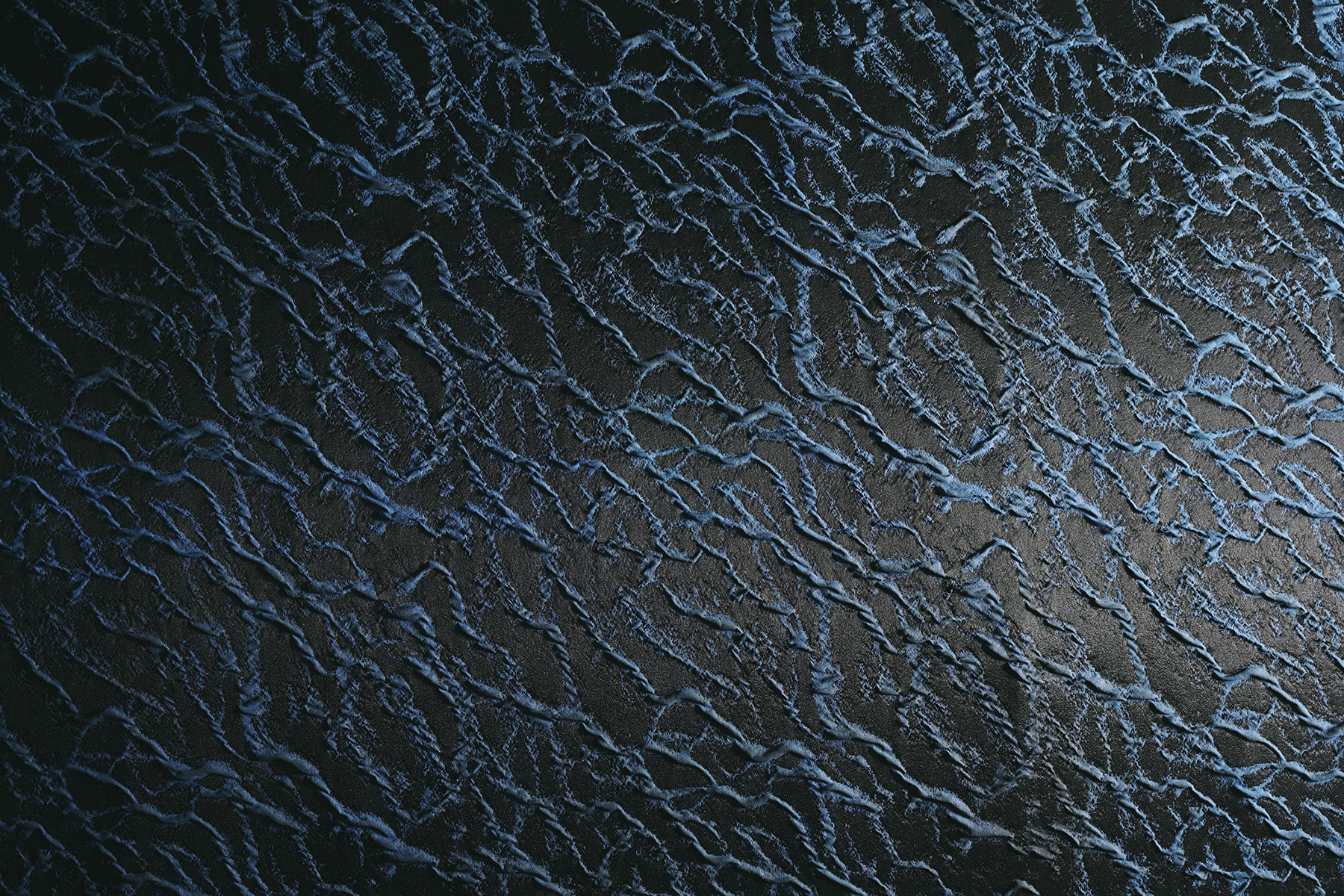

Ambient Weaving

Dialogue Human Body and Beauty of the Future

Daito Manabe (Media Artist, Rhizomatiks representative) × Masataka Hosoo (President and CEO, Hosoo Co., Ltd)

Hosoo: Today, we welcome Mr. Daito Manabe, Rhizomatiks representative. Mr. Manabe is a media artist and programmer engaged in experimental expressions across various fields, such as music, video, dance, and performance. We hope to explore the intersection where Mr. Manabe’s work and our activities merge and to discuss the “beauty” of the future.

Last year at Hosoo Gallery, we held an exhibition, Quasicrystal: In search of textiles using code, to present the result of our project aimed at creating, through collaboration with a mathematician and programmers, innovative weave structures that had never existed in history. What we found interesting in the project was that, among the structures newly created through calculation and programming, those that were in harmony formed patterns found in nature, like wood grain or earth texture. Through textile, we experienced, firsthand, the connection between mathematics and nature.

Manabe: In mathematics, there is a famous pattern called “fractal,” which was found while studying geometry. It is a pattern in which parts and the whole are “self-similar.” We can find many examples of fractals in nature. The Fibonacci sequence is one of them. It often happens that you thought you were studying mathematics but ended up solving or simulating nature. Such phenomenons remind me of mathematics’ mysteriousness, which I find intriguing.

It must have been an inspiring moment to see natural patterns emerge as you weave a textile.

Hosoo: I imagine that, when a textile is in harmony, it also produces a beautiful mathematical equation. We’ve been making what we believe to be beautiful in the field of textile, but through the project, we learned that mathematics, beauty, and nature are linked.

Manabe: I think it’s hard to escape from the kind of rules that lurk in the natural world as represented by mathematics.

Today’s art, especially contemporary art since Marcel Duchamp, has diverged from exploring beauty and moved toward being conceptual. But the beauty that art initially aimed for, I believe, was output produced by artists who interpreted in their own way mathematical harmony or mathematical concepts hidden in nature. Such works are not appreciated today. In other words, the art world does not particularly value them. Still, the beauty in mathematical harmony has existed since 5000 B.C.E. I imagine it would be around for another 5000 years.

Hosoo: From the standpoint of someone involved in the craft of weaving, I place great importance on the human body. When we judge something, we base our decisions on whether we find them beautiful. I’m a fan of contemporary art, but since 100 years ago when Duchamp came on the scene, the emphasis has been on concepts rather than the beauty of the works. I feel that the bodily senses, as well as factors like beauty or pleasingness, have been left behind.

That being said, in recent years, the field of contemporary art has been making approaches to the field of craft. I sense that there is a movement to recover the once-forgotten “bodily beauty.” Hosoo has collaborated with a contemporary artist, Teresita Fernández. Gerhard Richter has started making works using textiles. Art seems to be returning to craft.

Manabe: In that sense, we may be seeing a sort of backlash. I also think that, by using today’s technologies and methods, there are things we can rediscover in the traditional realm of craft. In particular, I imagine that 3D scanners and 3D printers are being used for experiments in the field of craft. Also, with the advancement of sensing technologies such as 3D measurement technology, sculptures and 3D modeling are being reevaluated.

Manabe: Since I write programs myself, I can usually complete most things on the computer. But instead of ending there, I return to the analog side, the real world, and try to create errors. For example, in my collaborations with dancers, I’m exploring the possibilities for new dance performances, like real dancers performing a choreography produced by machine learning.

Hosoo: While working on Quasicrystal, we saw weave structures that looked complete on the computer screen but didn’t work when woven as a substance, because the yarns failed due to the humidity or the silk’s property. I was fascinated by those things that were “beyond simulation.” The programmer and mathematician also went back and forth between digital and analog. They would write codes right by the loom and then weave a textile using those codes. If it didn’t work, they would try di erent codes. Indeed, from those errors, we were able to create a beauty that was at the extremity of harmony. As I was working on the project, I felt that iterating digital-analog sessions could be one way to explore textile.

Manabe: In the past, I, too, have created a programming language for an industrial sewing machine, although it was not as complicated as weaving (“Pa++ern 2009 [an esoteric language for embroidery]”). The project entailed developing a simple programming language and its environment for an industrial sewing machine, and I thought that the act of creating patterns through repetitive processes was in itself very programming-like and mathematical.

It was easy to create patterns on simulation software, but as soon as they were applied to actual needle movements, yarns snapped, or a needle broke from too much repetition. By converting something that was imagined digitally into something analog and physical, we encountered so many errors. It sometimes took us four or five hours to produce one T-shirt. So, I completely understand when you say you had many errors when turning something into a substance.

Manabe: After I started working on dance projects, my idea for visual things has changed quite a bit. I think it’s the same for those with visual impairment, but even when our eyes are closed, we can sense what a circle or square is like, for example. It is because we feel the shapes or space through muscle movement, not by vision through the retina. In choreography or dance, we feel with our muscles the visual expressions like geometric figures.

When you watch a dance, you only visually sense the movements, but when you move your body and dance, you notice that the choreography and dance have geometric meanings. This was my recent discovery.

Seeing also involves using the ciliary muscle to pull and loosen the lens to focus, so we use our muscles to focus on the object we are looking at. Recently, I have been rethinking the relationship between the body, mathematics, and beauty.

Hosoo: The history of textile tells us that the first loom was, in fact, the human body itself. You would wind the warp around your body to apply tension before weaving. Later in history, they extend the human body. Wooden frames were created, and weaving with a takabata floor loom began. In the modern era, the Industrial Revolution led to the invention of the power loom. Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, the first company in Japan to make power looms, moved on to use the technology to make automobiles. The automotive division was spun o and developed into today’s Toyota Motor Corporation.

So, the history of textile seems to tell us that technologies evolved as a result of expanding the human body in search of something better in their pursuit of ultimate beauty. The story about the invention of the computer, which was inspired by a Jacquard loom, is also symbolic.

Beauty and technology are closely related, but I don’t think the relationship is understood correctly today. The general public’s sensibility praises technology as something comprehensible but tends to consider beauty as something incomprehensible. Many people don’t understand that beauty and technology are linked.

Hosoo: In the context of dyeing and weaving, beauty and technology are one. In the search for beauty, the body was expanded, and new technologies were created. I would like to ask you about the relationship between beauty and technology, which I think is also related to your work.

Manabe: For example, there are recent cutting technologies like blockchain and NFT (Non-Fungible Token, non-fungible digital data using blockchain). But, what they produce with those technologies are images and video data. And their contents are often based on mathematical or geometric rules. When you think about it, humans started making drawings using mathematics or geometry in 5000 B.C.E. in Egypt. You could go as far as to say that the patterns produced have not changed.

Tools have changed, and what programming enables us to do is significant. Writing a program changes the scale of numbers because, for example, you can create 10,000 images at once by introducing iterative processing, whereas before, you had to do it one by one manually. But, what we are making are often patterns based on mathematics or geometry. This is true especially in the fields of generative art, interactive art, and media art. We may be progressing in one way, but the beauty itself has not changed.

The human-media relationship has evolved. Today there are graphics that would change according to the human movements or temperature, for example, but the basis for the output remains the same. When I think about what “eternal beauty” is, for me, it means mathematics. In particular, geometry.

Hosoo: What did you think of the exhibition Ambient Weaving?

Manabe: I thought it was very interesting, especially the graphical work that visualized environmental information. I was impressed by your exploration of how the environment and textile would come together to harmonize. I observed the exhibition as if it were a research laboratory. In the laboratory, you studied the ways to harmonize the environment and textile. The exhibition was like a “display of prototypes.” I have a feeling that the ideas found in those prototypes will develop into real clothes or will be implemented in society.

Hosoo: We conduct research and development under various themes, including ancient dyeing and bodily knowledge of the craftsmen. The pieces displayed in Ambient Weaving also used the knowledge obtained in other researches. In terms of research and development, we don’t just aim for high-tech, innovative outcomes but also research as much as possible the traditional dyeing and weaving culture, like natural dyeing and bleaching. What we intended to do was to present the resulting products in an exhibition as a contemporary way of expression that inherited such historical context.

Manabe: Textile has a very long history. I find it interesting that its basis has not changed at all, even though it has evolved by confronting technological progress and incorporating the cutting-edge technologies of each era.

There are many things that will disappear because the introduction of technologies changes them all too quickly. In terms of the media, the paper went out of fashion and books declined, causing the spread of digital media. However, things you wear, like clothes, are indispensable for us to live in the real world. I think that is what makes them different from others.

Today, many things that surround us are becoming digitized, and little analog items are left. I listen to streaming music and watch movies and read books digitally. But, even under such situations, things related to our body, like architecture or clothes, remain the same. The fact fascinates me.

Hosoo: I have a background in dyeing and weaving, so when I think about the environment, I trace back the history through the perspective of weaving. I believe we must go back to the culture that embraced craft, before the spread of mass-production and mass-consumption culture. By doing so, we can find not only beauty but also the richness of various kinds and the culture that values environmental harmony. The attitude of using good quality items for a long time is also something we must bring back. Nowadays, clothes are often marketed as having a small environmental impact, claiming that “this fiber will return to the earth” or “70% recycled.” It may appear to be environmentally friendly, but the system is based on the premise of “disposable.”

Manabe: If we tried to reduce the environmental impact only with a short-term perspective, we may make the wrong decision. I agree with you that we need to think about what will happen in the long run.

Hosoo: In the old days, the basic idea was to use a good-quality kimono for generations. A 14-meter-long piece of textile is cut into eight parts and assembled without any discarded parts. Unlike Western dressmaking, a kimono is purposely sewn for easy disassembly. Once it becomes dirty or worn o , you can take it apart and return it to pieces of textile, which can be washed and reassembled (araibari). In some cases, the frayed parts, like around the hip, are replaced when sewing the pieces back together. Rather than bringing it to completion, a kimono is made with room for dismantling, allowing us to keep using a good-quality piece. I believe that the kimono culture can question today’s society and present di erent ways of thinking.

I’d like to propose to our time the philosophy of craft. It is impossible to change the world by ourselves, but I believe the key is to form a group of collaborators and make a new trend. Many people now realize that “it is wrong and unsustainable to continue mass production and mass consumption.” Maybe we can accomplish what they couldn’t in the 19th century when William Morris of the Arts and Crafts movement was active or in the 20th century when Muneyoshi Yanagi and Kanjiro Kawai established the mingei (folk art) movement. It is our mission, too, to take on the challenge.