RESEARCH

Study on Early Modern Cloth

Study on Early Modern Cloth

Shinichiro Yoshida The existence of white exhibition

The room is so dark that it makes us feel slightly anxious. At the back of the room, we see an oblong object faintly gleaming white. It appears to be made of 20 tall pieces of fabric joined together. Each fabric piece has its unique, subtly different tone: some with a yellowish tint and others with a blackish tint. They are quietly standing at the far end of the gloomy room. The object reminds us of the moon floating in the air being elongated into a rectangle.

On the other side of the room are 14 pieces of the same-shaped cloth placed side by side, although they are brighter than the first ones. Here, too, the tone of each piece differs slightly. Adjacent to the room is a path leading to a dark space. On the wall of this cavelike space, another six pieces of similarly-shaped fabric are placed side by side. The darkness of the surrounding space seems to cause the pieces to appear as white cloths. In an even smaller space beyond the dark space, a tall video monitor displays the slides made up of texts and still images questioning anew what “white” entails. Being in a dark space only a few moments ago, the light from the monitor stimulates our eyes. At the same time, our concept of “white,” which we have taken for granted, is being overturned.

Coming back from the slide room to the previous room, the surrounding space appears whiter than before, and the six fabric pieces appear darker than the space, perhaps due to the impact of the light from the monitor. As we further retire to the large room, the white cloths remain perfectly still, but we get a feeling that their impression has changed. All we can hear in this space is the noise of

the air flowing through the building. It is just a dark room with white textiles placed next to each other. Nevertheless, we find it difficult to leave. We sit on one of the chairs facing the white cloths, turn our eyes back to the cloths, and look vacantly at them.

This may be the sort of place that could serve as a mediation space. Perhaps the sensation we feel here is similar to that of being inside a place of worship at the deepest hour of the night. Or the sensation may parallel that of doing tainai meguri [literally, walking around the womb] in places like the basement of a Buddhist temple. The white cloths, standing side by side, remain silent and still, showing faint whiteness. If the room were a little brighter, we might be able to see more of their details. The frustration seems to further arouse our interest.

The cloths may be trying to tell us something. Something, for example, that many of us have forgotten. They are about to talk to us about that sort of thing but will never begin to do so. This state is what prevents us from leaving.

But the force that keeps us here is not strong. The muted argument uttered by the cloths could not be captured with our mundane sensibility. We must remain in this dark, tranquil space for a little while and calm our minds to awaken our subdued interest in them. Why? Where does this “eloquence of silence” come from?

All the textiles displayed here—hemp cloths presumably from the 1800s—are from the collection of artist Shinichiro Yoshida.

For over 40 years, Yoshida has been collecting and studying Japanese textiles. He has exhibited Japanese hemp cloths at overseas museums, including the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco, as well as various museums in Japan. For this reason, he is often introduced as a private researcher of Japanese textiles.

As mentioned earlier, Yoshida uses his massive textile collection and performs microscopic examinations of the yarns pulled out of the textiles. The method has allowed his research to become aligned with reality and convincing that it overthrew the long-accepted ideas about hemp. According to Yoshida, he began the study as a “pastime,” but its influence has become significant. But, for Yoshida, all these research activities were just another step toward a bigger goal.

Yoshida started painting in his 20s and, at one point, naturally shifted to using white paints on white canvases. But after going through a near-death experience, he decided to travel to see Western contemporary art firsthand.

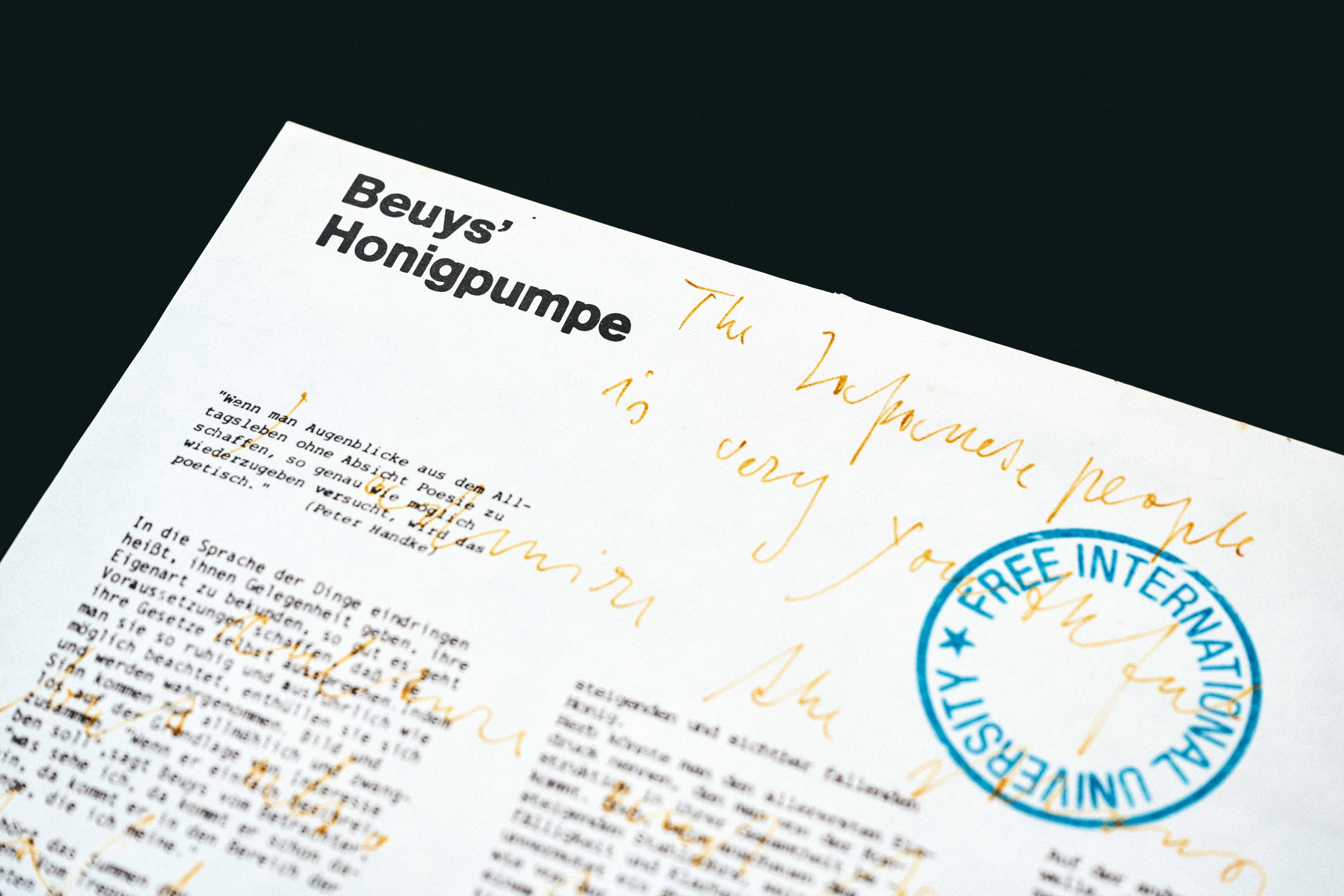

It was in 1977. Arriving at his first destination, Kassel in Germany, Yoshida had a crucial encounter there. At the time, the city was holding a contemporary art show Documenta 6. Shortly after his arrival, he met Joseph Beuys (1921–86). It was before the German artist became known in Japan. Winning Beuys’ favor, Yoshida decided to stay in Kassel with him for a while. Shortly after, Yoshida

showed Beuys the only white work he had brought with him, which got Beuys interested. However, when asked by Beuys, “Why white?” Yoshida was not able to answer. Beuys persistently asked, “How is the color linked to your roots?”

The incident gravely shocked Yoshida, who terminated his tour around the West and immediately returned home. Then, he began exploring his roots so he could answer Beuys’ questions and show

him his works once again. In the process, he started researching Japanese textiles. According to Yoshida, he was planning to move on to a different research topic after he understood enough about textiles. But the process took him much longer than he had expected. And before he knew it, several decades had passed, and he had become known as a textile researcher.

After about 30 years since he began his research, Yoshida was preparing an exhibition of hemp cloths at a museum when he glanced at a row of white cloths from the Edo period and felt something extraordinary in them. At this moment, he realized that this was where he could find what he had been pursuing all along: his ideal work. All he had to do was simply lay out white textiles, not draw on them. (Until then, he had continued to draw croquis sketches almost daily, pursuing the work that would satisfy himself.)

The first piece presented was White from 2017 (at Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]). Indeed, 40 years had passed since his first encounter with Beuys. White presented this time is an update to the original piece, and Black is its newly-created counterpart.

Yoshida explains that, when laying out the hemp cloths from different times and places, each piece shows its distinct white. The colors depend on conditions such as the type of hemp yarn, the tightness of twisting of fine-count, low-count, and warp yarns, and the density of weaving. “The differences imperceptible to the naked eye emerge as the subtle, yet unique, manifestation of each ‘white,’”* adds Yoshida.

The existence of white: this reticent piece provokes our thoughts endlessly. And in this work, Yoshida places his message for the future, just as Beuys did with the social sculpture he advocated.

*Shinichiro Yoshida, “On hemp fiber textiles,” Fabrics as Demiurges: The meaning of fabrics for mankind (Yamaguchi: Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, 2017)

—— I suddenly realized: if no white was the same, then what if it could be likened to a mind? Individual pieces of white cloth. At the YCAM exhibition, I laid out 58 pieces, but it could’ve been a hundred or a thousand; there is no limit. I think I can make it easier for you to understand by saying 58 minds, instead of 58 white cloth pieces.

People see them as the “same white cloths.” In other words, if people consider 58 minds as suffering the same exact distress, just as they perceive the 58 white textiles as being identical to each other, then it can’t be the right way to give advice. We must recognize that there are 58 minds. There are 58 distinct sufferings. There is nothing more absurd than treating them as single suffering to communicate with the sufferers. That would encourage or solve nothing.

(……)

Watching the news on TV, the old and the young are all talking about and acting on things like the global environment, sustainable energy for the future, and medical care, although I’m not sure how

much they really understand. Young people like that often come to see me, and what we discuss seems to overlap considerably with the issues that I just mentioned. Young people are beginning to realize [that these issues exist]. We had known, too, but older people grudged doing anything and closed our eyes against them. We bundled them together as a single “white,” did our job, and got paid to live. But I think we are entering an era that no longer allows such behavior. Soon, we’ll have to accept that there are different “whites.” They are also about social issues, human life, and human rights. In thinking about such issues in terms of “whites,” my White piece conveys a message: “Can you live with your eyes closed, treating everything as an indistinguishable ‘white’?”

Excerpts from an interview book. Shinichiro Yoshida | The existence of white